This is the story of one of Italian football’s forgotten pioneers. A man from humble beginnings in Nottingham, England. His employment took him to northern Italy more than a century ago, where he proceeded to play a pivotal role in the development of Italy’s national game. Whilst the narrative may sound familiar, the name will probably not be. This is the story of Harry Goodley.

Once Upon a Time in the East Midlands

Henry “Harry” Goodley was born on 30th March 1878, into a striving working-class family in central Nottingham. Harry had grown up, along with his three siblings, in a modest terraced home at 55 Gawthorne Street, Basford. His father’s employment as a mechanical engineer in the lace-making industry afforded the family a degree of comfort, but with four hungry mouths to feed, his wife also went out to work in the lace factories.

Lace-making was big business in Nottingham at that time. The Lace Market represented the beating heart of the city. There were hundreds of manufacturers and vast swathes the city’s residents were employed in the industry. Goodley senior worked for Birkin’s, a successful manufacturer whose interests had spread from their Nottingham roots across Europe and over to America. Harry had seen first-hand the opportunities proffered to a man equipped with the skills demanded by this new industrial dawn. His father’s work had taken him to France at the end of the 19th century, where Harry’s youngest brother had been born.

Harry recognised that work could be his own passport to fulfill a deeply-ingrained sense of adventure. Upon leaving school, he duly followed in his father’s footsteps as an apprentice engineer with Birkin’s. His choice paid off handsomely. At the tender age of 17, Harry was on his way to America to help install lace-making machinery in Boston, Massachusetts. And by his early twenties, Harry was truly forging his path in life, leaving his family and home city to take up work as an engine fitter in Sheffield.

However, these sporadic foreign trips had only intensified young Harry’s appetite for exploration and adventure. It was clear his horizons were broader than just the next county. In 1903, aged 25, he accepted a job working for the Swiss textile entrepreneur Alfred Dick in Turin. With a limited grasp of either the Italian language or the culture, it was a bold decision, although one not without precedent.

Goodley’s home city of Nottingham and Turin had forged strong connections as a consequence of their shared expertise in textiles production. A decade earlier, Herbert Kilpin, the man who went on to found AC Milan, had trodden the very same path as an economic migrant. Kilpin’s childhood home on Mansfield Road was just a mile from Gawthorne Street and, although not contemporaries, they were members of the same professional circle and would have kicked a ball on the very same Forest Recreation Ground.

An introduction to Juventus Football Club

As Goodley packed his bags ahead of his voyage to Italy, he received an unexpected request from Turin. Another Nottingham native and node of the textiles network, Tom Gordon Savage, was in the process of procuring a new set of football shirts to replace the faded pink and black garments worn by his team, Juventus Football Club.

Savage had been an accomplished footballer, enjoying success with Torino FCC, Internazionale Torino and finally Juventus, for whom he appeared in the Italian Championship in 1901. Whilst Savage’s playing days had come to an end, he remained involved with Juventus and was making use of his professional contacts back in Nottingham to source a replacement kit. Legend has it that he had his heart set on red jerseys, but settled for the only available alternative; the black and white stripes of Notts County.

Goodley’s new boss, Alfred Dick, was not only a successful industrialist but also happened to be a director of Juventus. He was known to mix business with pleasure and there had been a steady flow of men from his factory floor to the football pitch. With Goodley on his way from Nottingham to Turin shortly, one theory goes that he was asked to transport the new kit, along with his worldly belongings over to Italy. With that twist of fate, Goodley duly delivered Juventus’ first black and white kit and in doing so became deeply entwined in the birth of the bianconeri.

A dedicated club servant

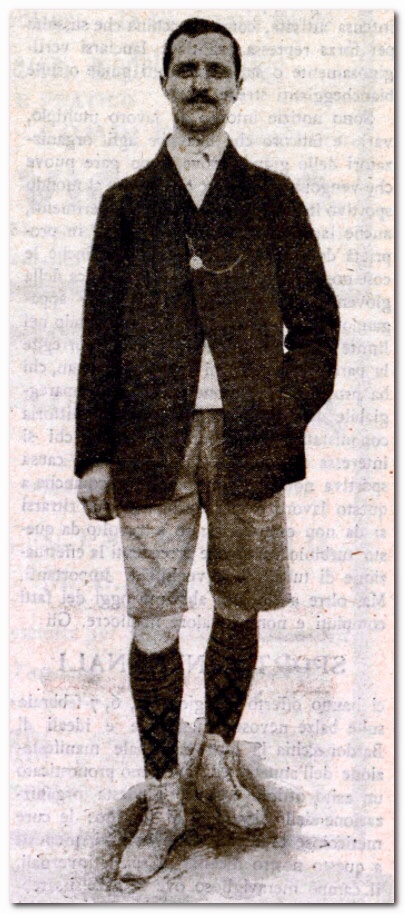

As a younger man, Goodley had been an enthusiastic amateur football player, turning out for Basford Wanderers and Notts Rangers in the local leagues. So, upon arrival in Turin, what better way to make connections in a new city than to join his employer’s football club? Despite Harry’s obvious fervour for the game and the somewhat lower standards of play, his career in Turin was short-lived.

In fact, his sole appearance came soon after arriving from England, in a friendly match against Club Athletique di Ginevra in April 1903. Juventus had the final of the Italian Championship the following day, so their ranks for this fixture were swelled with reserves and guest players from across Turin. The harsh reality was that, for all his zeal, Goodley just did not cut it as a player.

Goodley remained undeterred. This setback would not stifle his passion for the game and he continued to offer his services to Juventus. The running of the football club in this era was a collective endeavour, reliant on the skills, commitment, and flexibility of a relatively small group of people to make it all work. He was on hand to help the club in whatever way he could.

Italian football was still in its infancy around this time. There were few spectators, small numbers of people played regularly and a smaller number still had a full grasp of the rules. As such, each club was required to provide an affiliated referee, usually a club member or retired player, who would officiate other matches, and sometimes those of his own team. This was the ideal role for Goodley. He knew the rules inside out – and his austere demeanour was perfect for the demands of the job. Taking up the whistle enabled him to indulge his interest in the game, whilst also enhancing his position of standing within the club.

Goodley never again got to pull on the black and white stripes himself, but he was asked to do the next best thing. Alongside Savage, Goodley had been informally coaching Juventus’ younger players where he demonstrated a natural aptitude for the strategy of the game. It was a mark of the esteem in which he was held within the club that Goodley was formally invited to coach the senior team in 1907-08. In this capacity, he steered Juventus to victory in the Campionato Federale – a supposedly inferior championship which permitted the participation of foreign players – defeating Andrea Doria in the final.

The Englishman had also foreseen the developmental benefits of pitting his club against a higher standard of opposition. By his own account, Goodley had been instrumental in encouraging the Italian Federation to invite foreign teams to tour Italy. One such example, in which Goodley was thought to be pivotal was the Sir Thomas Lipton Trophy. This was a pre-cursor to competitive pan-European football competition, which saw English, Swiss and German teams travel to Turin to compete against his club.

Making waves in the Federation

By now Goodley had firmly established himself as a key figure not only at Juventus but within Italian football more widely. In his refereeing of games across the north of Italy, he became renowned for his composure and integrity, both on and off the pitch. As the Italian national team prepared for their inaugural international fixture in May 1910, against France, they turned to Goodley as the man to take charge of the match.

His nationality made him a more neutral choice than an Italian official. Indeed, Goodley took his impartiality very seriously and, keen to ward off any murmurings of favouritism from the French, he insisted on making payment for a panino and beer that the hosts had offered to him. Bedecked in all white Italy, crashed to a disappointing 6-2 defeat at Arena Civica, but history had been made and Goodley, quite literally, was at the centre of it all.

Referees were seen as figures of great importance in those early days. The nomadic role they played in travelling between cities, officiating different matches also gave them a unique perspective on the standards of play and the players themselves. Unconventional as it seems today, it is perhaps understandable that the Federation looked to this knowledgeable group to make selection decisions for the national team. Ahead of the Olympic Games in 1912 and again in 1913, Goodley was invited to sit on the technical selection committee for the Italian national team.

Goodley’s impartiality would be most sternly tested when he was asked to officiate for the national team one final time. Italy were to face Belgium in the opening ceremony of Turin’s Stadio Piazza D’Armi in May 1913. Under the watchful gaze of dignitaries, the pressure was on for Italy to record their maiden victory on home soil. The choice of Goodley as the referee in his home city was taken on merit, but it was a perplexing decision nonetheless, given his continuing role as part of La Nazionale’s selection committee.

In a closely fought contest, Italy prevailed by one goal to nil. As the Italian spectators and players rejoiced around him, Goodley cut an impassive figure, seemingly indifferent to the magnitude of this fateful moment in his adopted city. Upon leaving the field, Goodley turned to his Juventus colleagues and remarked “Sono contento – li gela – di aver concluso in questo modo la mia permanenza a Torino. Ora posso tornare soddisfatto nella mia patria”. All became clear. This moment of pride was tinged with personal regret for Goodley, as he revealed that he would soon be leaving Turin for good.

An abrupt farewell

It came as a shock to many at Juventus that they would be losing this loyal servant. He had been a Turin resident for a decade and had laid down roots here. He had met and married his Italian sweetheart, Erina Parigi, shortly after arriving from England and together they had started a family. First came daughters Evelina (1905) and Ida (1907), then there was a son, Charles, in 1912. Turin was his home, but Goodley’s overwhelming spirit of adventure had come calling once again.

A group of Juventus members decided to honour the departure of their friend by presenting him with a gold watch in recognition of his services to the club. They arranged for financial contributions to be collected from club members. Meanwhile, the local newspaper Gazzetta del Popolo, for whom Goodley had penned a regular sports column, also heard of the initiative and offered to contribute as well.

However, Goodley left Turin in a hurry, before his colleagues had the opportunity to present the watch to him. The club tried in vain to contact him through friends, relatives and former addresses, but their endeavours came to nothing. Then, the outbreak of the Great War in 1914 put all of those efforts on hold. Naturally, the fate of their friend was never far from their minds.

Then, in 1917 came the news they had dreaded. Unconfirmed reports reached Turin that Harry Goodley had perished on the front line in France. They were understandably distraught, particularly since they’d never had a chance to say goodbye properly. His friends attached a card to the watch reading “Destinato a Mister Goodley, forse morto” (Destined for Mr Goodley, perhaps dead) and entrusted it to the possession of the offices of Gazzetta del Popolo, where it was placed in a drawer seemingly to be forgotten.

The most unexpected of returns

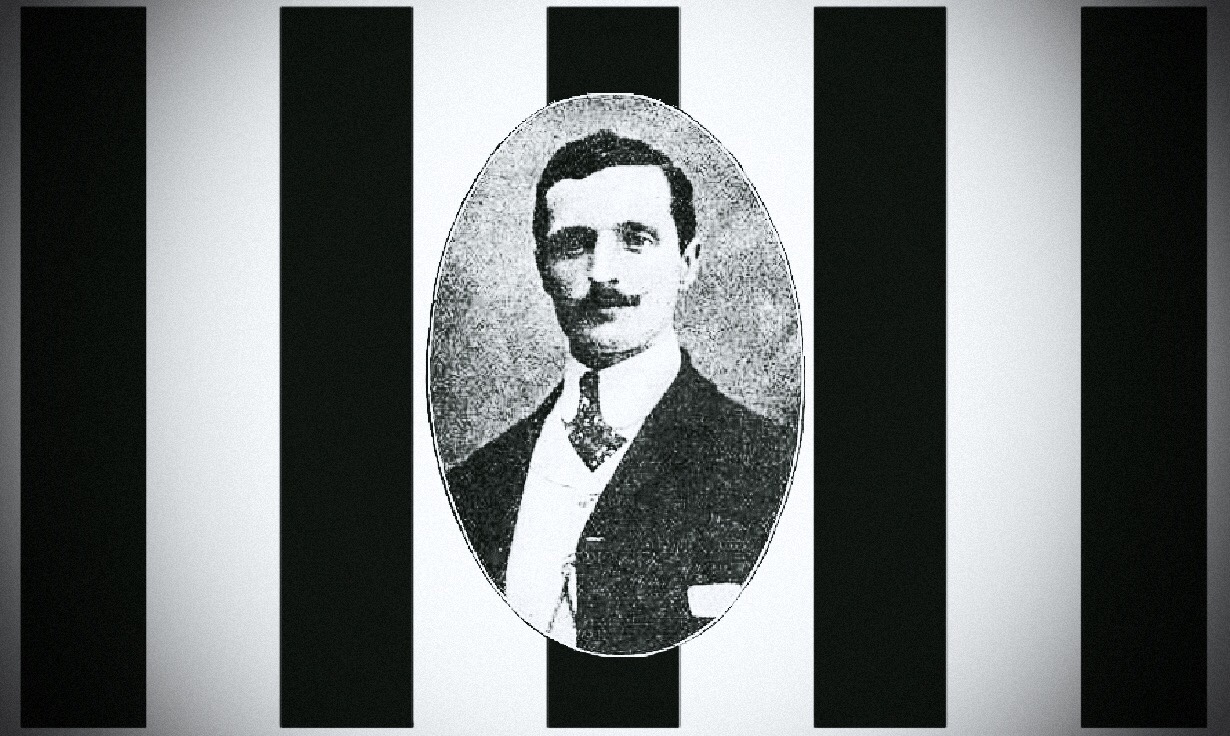

Some seventeen years passed and the memory of Goodley in Turin had begun to fade before his story took the most wonderful twist. One day in 1930, a middle-aged gentleman arrived unannounced at the Juventus club offices. He had a distinguished look about him, spoke good Italian, but with a foreign accent. He introduced himself as Harry Goodley. Harry Goodley!

A pulse of excitement rippled through the club and word soon got out to Goodley’s former friends and acquaintances that he was back. Naturally, the euphoria of his unexpected re-appearance was accompanied by a torrent of questions about the intervening years. Why did he leave Turin so abruptly? What about the stories from France? How were Erina and the children?

His original destination had been Petrograd (St Petersburg) in Russia for business. But his arrival there coincided with the early events of the Russian Revolution. As the Russian monarchy fell, Goodley became trapped in the country, taking some time before he was able to return to England. Shortly afterwards, the outbreak of war called him into active service in France. As Goodley stoically recounted his tale, his friends were immediately reminded of his unflappable disposition.

As the conversation went on, someone suddenly remembered the watch. They dashed over to the newspaper’s offices where, after a frantic search, they find it, in the drawer where it had been left over a decade ago. The watch was finally presented to Goodley, at which point his characteristically unemotive façade cracked. His friends had never seen him like this. Goodley confessed, “Quest’orologio mi ricorda i giorni oiu belli della mia vita” (this watch reminds me of the best days of my life).

With this belated closure to his time at Juventus, this is where the story ends for one of calcio’s forgotten pioneers. Following his brief visit to Turin, Goodley returned to Nottingham to put his energies into his work. He established the Goodley Electric Jacquard Company along with his son, patenting lace-making machines in the UK and US, operating out of the very same Victoria Works in Nottingham where he began his apprenticeship all those years ago.

The final act

In January 1951 a short notice appeared in Turin’s La Stampa Sportiva announcing the passing of Harry Goodley. At the ripe old age of 72, he had survived many of his contemporaries from his time in the city. Despite the decisive role Harry had played in building one of the world’s great footballing institutions he died in relative anonymity. He saw out his final days with his sweetheart, Erina, at 27 Central Avenue in Nottingham, a modest bungalow located just a few hundred metres from his childhood home.

If you enjoyed this, read about Juve’s exploits in the fabulously named Palla D’Oro Moët et Chandon.

With huge thanks to Roger Stirland and Victor Vegan for sharing their research, and to Robert Nieri for his encouragement.

Landmarks of Goodley’s Nottingham

1 Comment