Frank Rawcliffe was that rare breed of an Englishman who flourished in Italy.

Plucked from the lower reaches of the Football League, his fearsome centre-forward play and predatory instincts in front of goal earned him a place in Alessandrian hearts. His rambunctious brilliance was tempered by a casual attitude towards physical fitness and a spate of debilitating injuries. But what he lacked in professionalism and good fortune, he compensated for with a roguish charm. Imagine, if you will, a hybrid between John Charles and Paul Gascoigne, slugging it out in Italy’s second tier.

Born in 1921, Rawcliffe spent his earliest years in Cardiff before his family moved north to Wallasey. His performances at wing half for Cheshire Schools caught the attention of local club Tranmere Rovers, who engaged him on amateur terms. Before his feet had touched the ground, young Frank had been thrust him into senior football with the club’s reserve team at the tender age of just 14.

He was a precocious talent, perhaps one of the original wonder-kids. A horde of suitors from further up the Football League hierarchy were circling even before he’d made his debut. It was First Division Wolves who prevailed in January 1939, paying a fee of £3,000 and in doing so breaking the record for a player without a Football League appearance to his name. Under the nurturing gaze of Wolves’ pioneering manager Major Frank Buckley, Rawcliffe appeared to have a bright future ahead of him.

However, just as the next chapter of his career was beginning to take shape the onset of war precipitated the suspension of the Football League. Of the many cruelties of conflict, the sacrifice of a young footballer’s career comes some way down the list, but there was no doubting the detriment caused to Rawcliffe by this hiatus. From playing alongside Stan Cullis and Billy Wright, Rawcliffe swiftly found himself engaged in the altogether less glamorous role of a docks labourer back on Merseyside.

Rawcliffe’s team mates fondly recall his genial spirit and a fondness for playing practical jokes in the dressing room; a particular favourite of his was hiding or swapping others players’ clothes. However, during those war-interrupted years, this mischievous streak got the better of Rawcliffe, resulting in two regrettable brushes with the law. Firstly, he was fined by the police having been caught pilfering corned beef and sugar from the docks. Later, towards the end of the war, Rawcliffe and a couple of friends were handed three-month jail sentences after being convicted of the opportunist theft of several geese from neighbouring back yards. A remorseful Rawcliffe pleaded guilty, attributing his actions to a night on the ale.

After his spell on the docks, Rawcliffe was conscripted to the Royal Air Force where he became a sought-after guest player in unofficial war time football competitions. Rawcliffe, now converted to a centre-forward, turned out variously for Derby, Crewe, Blackburn, Notts County, Colchester United and even played in a Merseyside derby for the red half of the city. However, Rawcliffe lost many of his best years to the conflict, and by the time the Football League finally resumed, the teenage wonder-kid was in his mid-twenties with only fragments of a career under his belt.

The resumption of competitive football in 1946-47 presented the opportunity for a fresh start. Rawcliffe signed for Division Two Newport County, where he finished as top scorer with a tally of 14 goals in 37 appearances. From there, followed seasons with Swansea Town (16 in 26) and Aldershot (17 in 38), therein illustrating two recurring themes of Rawcliffe’s distorted career. Firstly, he was a proven goal scorer, consistently hitting double figures, even in struggling teams. Notwithstanding these feats, he never lasted long at any club. Three different clubs in three seasons, in an era of more enduring associations between club and player, led him to be described as “a rolling stone” by one newspaper.

Meanwhile, over in Italy, Alessandria were fighting the sands of change, having been a club of great eminence during the 1920s and 1930s. They formed part of the famed Quadrilatero Piemontese along with Novara, Pro Vercelli and Casale, a collection of small-town teams from the north that consistently punched above their weight. As the grip of professionalism tightened on Italian football, the pendulum was swinging away from these small historic clubs towards those in the bigger cities backed by new industrial riches.

Following relegation from Serie A in 1948, Alessandria handed the task of restoring their top flight status to an Englishman named Bert Flatley. Flatley was an unlikely appointment. At just 30 years of age, his playing career in England had been curtailed by war and injury and he had no formal coaching experience. However, this was an era where a British passport still bestowed a certain amount gravitas, allowing the holder to trade on the title of inventor of the game.

Flatley looked to Britain as he sought to strengthen his Alessandria team, setting his sights on a young Scottish forward from Doncaster Rovers named Pat Gillespie. Terms had been agreed on a three-year contract and Gillespie’s plane tickets to Italy were booked…until the move was halted by Scottish junior club Blantyre Victoria. A bitter row erupted when The Vics claimed to hold the player’s registration and were therefore due a cut of the transfer fee.

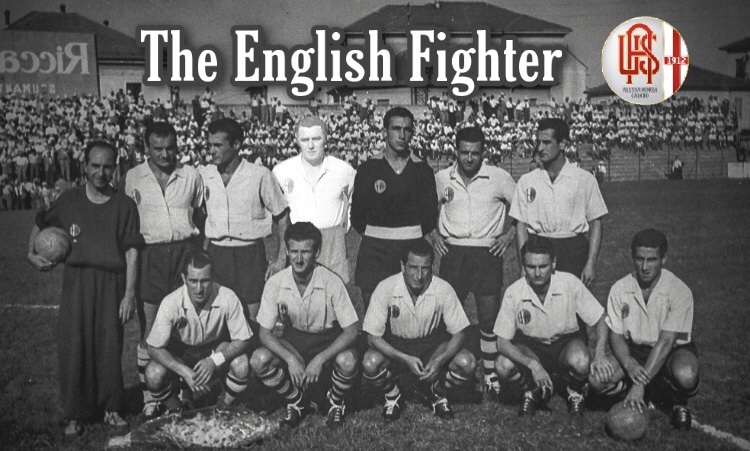

After a protracted dispute, Gillespie’s transfer was eventually cancelled and Flatley turned his attention instead to 27-year-old Rawcliffe, who had recently been made available for transfer by Aldershot. He was an unknown quantity in Italy, but made quite an impression with club officials and new team mates when he arrived. He was fair-skinned, around 6 feet tall with a broad, bulging physique that led La Stampa to remark “he looked more like a fighter than a footballer”.

Rawcliffe stepped straight into the centre-forward position, and showed there was a lot more to his game than just an imposing physical presence. The goals soon began to flow; a brace against Napoli, followed by another against Reggiana in his next match. Flatley and Alessandria were purring, but Rawcliffe didn’t have it all his own way. Against Brescia, he endured a torrid afternoon, being denied two clear penalties. His grievance was compounded when he was later cited in the referee’s report for diving (or, more formally, “foul simulation”). Alessandria’s letter of appeal to the FIGC had no effect and Rawcliffe served a one game ban.

This setback, along with an enforced return visit to England to deal with a family matter, stymied Rawcliffe’s progress, but only temporarily. On his return to Italy, he scored 7 goals in his next 8 matches. Here was a paradox; a player at first pass not fit to grace a football field, an individual characterised by the local newspaper as moving with “excessive slowness” (no doubt an artefact of his weakness for the local wine and culinary fare; the agnolotti a particular favourite of his). On the other hand, his heading and shooting abilities were outstanding and his goal-scoring record spoke for itself. And when he was at his rambunctious, combative best Alessandria’s whole forward-line clicked.

In spite of Rawcliffe’s devastating form in front of goal, an inglorious mid-season run of 8 defeats in 10 games saw Alessandria slide towards the foot of Serie B. Their away performances had been wretched all season, but problems began to mount when their home form waned too. Alessandria’s matches were entertaining if nothing else; suffering several thrashings, but also chalking up a couple of five-goal victories. Flatley was peddling anti-Catenaccio in Piemonte.

Towards the end of April, disaster struck for both Rawcliffe and Alessandria. The forward suffered a serious knee injury in a clash with the Udinese goalkeeper, which brought his season to a premature conclusion. I Grigi were suddenly looking down the barrel of a difficult run-in without their leading marksman. Flatley’s men gallantly fought on, but found themselves in the fifth and final relegation spot come season end. Rawcliffe’s remarkable record of 18 goals in 27 starts proved a mere footnote in a sombre season for the club.

With Flatley soon departed, the prospect of a year in Serie C held limited attraction for Rawcliffe who returned to England during the summer to consider his options. He took up a player-coach role with amateur club South Liverpool, whereupon the depths of his physical deterioration became apparent. Rawcliffe had the waistline and athleticism of a man well beyond his 29 years, yet that deadly goal-scorer’s instinct was still present. Clearly operating some way below his level in the Cheshire League, he struck 19 goals in just 15 games.

However, Rawcliffe was still under contract in Italy and was summoned back to Alessandria in the late autumn to bolster their Serie C promotion push. It demonstrates the esteem in which he was held that I Grigi offered him a bounty of half a million lire, along with a promise to tear up the remainder of his contract at the end of the season, if he returned. It was a significant gamble for a club in a parlous financial state, but they knew what Rawcliffe could bring to the team.

An exultant crowd descended upon Alessandria’s training ground to mark the return of their English fighter. Expectations were running high, but when he eventually turned up (arriving a day late owing to a delayed Channel crossing), the club were mortified to see the bloated condition of their supposed saviour. The disappointment was palpable, as his lacklustre performances in training quickly dispelled any feint hopes he could play an immediate role in their promotion challenge. The newspapers scathingly speculating that it would take at least a month before he was ready for competitive action.

Rawcliffe was ordered into an intensive fitness regime with the ambition of bringing his weight down to a more acceptable 80 kg, ahead of his return to the first team. By mid-December 1950, in his second game back, he provided a glimpse of why Alessandria had fought so hard to bring him back; Rawcliffe bagged four goals in a 7-1 drubbing of Magenta AC. However, his tub-thumping performance against a struggling team belied a chronic lack of form and fitness. Rawcliffe managed just two more goal-less appearances before sustaining a serious injury which once again put paid to his season. And ultimately to his time in Italy.

Alessandria faltered to a fourth-place finish, consigning them to another year in the purgatory of Serie C. Rawcliffe returned to England, but any hopes of rekindling his professional career in the Football League were dashed when Alessandria reneged on their earlier agreement by withholding his registration. Rawcliffe appeared twice more for South Liverpool in April 1951 before disappearing from the football landscape altogether at the age of just 29.

It wasn’t supposed to turn out like this for the wonder-kid from the Wirral. A promising football career decimated by war and injury. If it hadn’t been for those lost years, who knows what heights he could have ascended? As it was, the themes of misfortune and unfulfilled potential were heartbreakingly mirrored in his life outside the game. On the 4th September 1958, Rawcliffe died at the tragically young age of 36, leaving behind a wife and four young children.

Frank Rawcliffe: perhaps England’s finest Italian export you’ve never heard of.

I owe huge thanks to Paul Crankshaw for his diligent research and in particular for untying the knot of Frank’s early and later life. Similarly, I am indebted to the excellent museogrigio.it website and the British Newspaper and La Stampa archives. Thanks also to Mal Flanagan from South Liverpool FC for supplying statistics and insights, drawing from the book ‘Rest in Pieces’ by Hyder Jawad. Finally, thank you to members of the Football Historians Group for their assistance, including Jonny Stokkeland, Orjan Hansson and Paul Lee.

Annex: Key Events & Playing Career

- Frank Rawcliffe was born on 10th December 1921. His birth was registered in Cardiff under his mother’s surname “Dooley”, but he later adopted his grandmother’s maiden name “Rawcliffe”

- In 1933 Frank plays for the Cheshire schoolboy’s representative team, aged 12 years

- In 1935, Frank’s mother Clara married his step-father George Woodward

- In 1936, Frank makes his debut as an amateur for Tranmere’s reserve team age 14-and-a-half

- In 1938, on his 17th birthday, Frank turns professional with Tranmere

- In 1939, Rawcliffe lined up for Wolves in a friendly against Birmingham alongside Stan Cullis and Billy Wright; the latter making his first appearance at Molineux.

- Frank married Amy Mainwood in Wolverhampton in 1939. And their first child, John, arrived in 1940, followed by Valerie (1942), Ann (1943) and finally Derek (1944).

- In 1940, Frank and his burgeoning family were living at 59 Urmson Road, Wallasey

- In 1941, a 19-year-old Frank was fined £5 by Birkenhead Police Court after being found to have stolen four tins of corned beef, 3lbs of sugar and some cheese from the docks. The newspaper reported: “Rawcliffe was seen leaving the docks…his pockets were bulky and he was stopped. He admitted taking the goods. He is not the usual type of docks pilferer and has given every assistance to the police. Rawcliffe told the court he was sorry and that it would not happen again”

- In 1945, Frank pleaded guilty to the theft of three geese from back yards close to his home in Hertford Street, Wallasey. When interviewed by police, Rawcliffe said the thefts would never had happened had they not “had some drink”

- In 1948, the deal to take Pat Gillespie from Doncaster to Alessandria collapses, opening the way for Rawcliffe. Gillespie had played under his step-father’s surname “McDade” for Scottish junior club Blantyre Victoria, who still held his registration. After initially threatening to quit football altogether over the Alessandria saga, Gillespie went on to convert from a forward to a goalkeeper for Doncaster and later Arbroath

- In 1951, Frank is linked with a return to professional football with Scunthorpe United

- Frank died on 4th September 1958 and was cremated at Anfield Crematorium

Playing Record (incomplete wartime statistics in italics)

- 1938-1939 Tranmere Rovers: 0 app

- 1939-1940 Wolverhampton Wanderers: 0 app (signed for £3,000)

- 1940 Southport: 2 apps, 0 goals

- 1942 Chester (v Oldham & Tranmere)

- 1942 Crewe Alexandra (v Everton)

- 1943 Southport (v Oldham)

- 1943 Derby County (v Chesterfield)

- 1943 Crewe Alexandra (v Tranmere)

- Feb 1943 Notts County: 8 apps, 3 goals

- 1943-1944 Notts County: 8 apps, 2 goals

- 1944 Stockport County: 2 apps, 2 goals

- 1944 Liverpool (v Everton)

- 1945 Blackburn Rovers (v Manchester City)

- 1944-45 Crewe Alexandra

- Aug – Nov 1945 South Liverpool: 13 apps, 6 goals

- Feb – Apr 1946 Colchester United: 11 apps, 3 goals

- 1946-1947 Newport County: 37 apps, 14 goals (signed for £250)

- 1947-1948 Swansea Town: 26 apps, 16 goals

- 1948-1949 Aldershot: 38 apps, 15 goals

- 1949-1950 Alessandria (ITA): 27 apps, 19 goals

- Aug – Dec 1950 South Liverpool: 19 apps, 15 goals

- Dec 1950 – Apr 1951 Alessandria (ITA): 4 apps, 4 goals

- Apr 1951 South Liverpool: 2 apps, 0 goals

Frank Rawcliffe was my dad’s dad.It was lovely reading about him.Alli knew was that he was a footballer.Im so proud of my grandad and just even though he died young your article makes me know more about him.

LikeLike

My pleasure Veronica – I’m glad the article found its way to Frank’s family. He sounded like quite a character!

LikeLike

Hi veronica, Cousin Ian from Wrexham. Its been great reading through all of this his daughter Ann is also fascinated piecing together the history.

LikeLike

Fascinating finding out about our Grandads History.

LikeLike

Hello.Just read the above and this is my mothers cousun.My mum is 97 years old and resides in a care home in Scarborough.She said he was a great footballer and a character too.

LikeLiked by 1 person

My name is Valerie Macfarlane Im Frank Rawcliffes Daughter i live in the Isle of man 80 years old.

I went to live with my mum and dad in Italy when he was plating football out there.

LikeLike

Hi Angela , grands daughter Ann would love to find out more about your mother

LikeLike